Russell Harris QC considers how the Planning System and a C21st Century "New Deal" would aid post COVID economic recovery.

My first ever memory is of a large, yellow bulldozer razing an entire street to the ground. It was traumatic. I was watching from an upstairs bedroom just one street, one back to back yard, away. Union Street Pontlottyn, part of the very fabric of my tiny universe was flattened. Very quickly. The sight was unforgettable (for me at least); the noise and the vibration unbearable. So too was the thought that Wine Street and Bridge Street beyond it to the north had already been “taken” from me and that High Street, the street from which I was watching was soon to follow.

I loved that house in High Street, Pontlottyn. I loved its people, four generations deep, its smells, its songs, its comings and goings, its perch on an unfeasibly vertiginous slope, where people sat on chairs placed outside and chatted, whatever the season. I couldn’t see why any of this had to be destroyed. I was 6 and I cried.

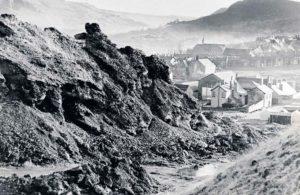

Pontlottyn, looking south at slum clearance area just pre- demolition from the iron ore waste tip: 1967.

Of course, not everyone saw it my way. The High Street house had no bathroom. It was heated only by its coal fires. It was damp. The roof leaked when it rained. Books smelled. Walls smelled, but differently and were cigarette paper thin. The neighbours were noisy. There were rats in the yard: sometimes worse. There was a battered upright piano: out of tune. The hardworking, underground-shift-working people who lived here deserved better.

These streets, which had been constructed with great speed by the mine owners in the coal and iron rush of the 1830s were “condemned” (along with thousands of others in the Valleys) as a result of mid-century slum clearance legislation. Three Acts of Parliament sought to require houses “not fit for human habitation” to be demolished and replaced and also, in language which says much about the time, outlawed the “erection of any back to back houses intended to be used as dwellings for the working classes.”( e.g S.5 Housing Act 1957).

Pontlottyn, looking south at slum clearance area just pre- demolition from the iron ore waste tip: 1967.

Of course, not everyone saw it my way. The High Street house had no bathroom. It was heated only by its coal fires. It was damp. The roof leaked when it rained. Books smelled. Walls smelled, but differently and were cigarette paper thin. The neighbours were noisy. There were rats in the yard: sometimes worse. There was a battered upright piano: out of tune. The hardworking, underground-shift-working people who lived here deserved better.

These streets, which had been constructed with great speed by the mine owners in the coal and iron rush of the 1830s were “condemned” (along with thousands of others in the Valleys) as a result of mid-century slum clearance legislation. Three Acts of Parliament sought to require houses “not fit for human habitation” to be demolished and replaced and also, in language which says much about the time, outlawed the “erection of any back to back houses intended to be used as dwellings for the working classes.”( e.g S.5 Housing Act 1957).

Bridge Street, Pontlottyn c 1961

In the place of these streets and others, Council Houses were built by the Gelligaer Urban District Council. This was the post-war planning system at its best. It was doing big things, urgent things, quickly. My grandparents moved from the coal board house I loved in High Street to a council house in the new Wine Street. This time they had a bathroom, an inside toilet, central heating and large picture windows through which the budgie used to fly and return. The piano remained: still out of tune. I loved it there too.

By the mid 1970s as a result of this process a very large percentage of all homes in my home town were council homes: homes built in the place of the demolished back to backs or on the sites of the redundant mine buildings. (Pontlottyn and Rhymney had an incredible 31 pits between them just by 1833). I don’t know exactly how these new houses are faring today, 50 years on. But, at the time, they were new, clean, convenient, safe and healthy. They also came with a new library, a community centre, new changing rooms at the “Rec” and a rather grandly titled “snooker hall”. They formed an important part of the community as a whole.

Bridge Street, Pontlottyn c 1961

In the place of these streets and others, Council Houses were built by the Gelligaer Urban District Council. This was the post-war planning system at its best. It was doing big things, urgent things, quickly. My grandparents moved from the coal board house I loved in High Street to a council house in the new Wine Street. This time they had a bathroom, an inside toilet, central heating and large picture windows through which the budgie used to fly and return. The piano remained: still out of tune. I loved it there too.

By the mid 1970s as a result of this process a very large percentage of all homes in my home town were council homes: homes built in the place of the demolished back to backs or on the sites of the redundant mine buildings. (Pontlottyn and Rhymney had an incredible 31 pits between them just by 1833). I don’t know exactly how these new houses are faring today, 50 years on. But, at the time, they were new, clean, convenient, safe and healthy. They also came with a new library, a community centre, new changing rooms at the “Rec” and a rather grandly titled “snooker hall”. They formed an important part of the community as a whole.

Pontlottyn 1983. The Council homes behind the shops and up on the Hill at Brynglas

There was no stigma attached to living in a council house. The majority of pupils in every class in the newly constructed Pontlottyn Junior Mixed School were council-housed. It was a stable, healthy, integrated and forward thinking community: a community that thanks to the new housing, the NHS and the Education Acts looked after itself and prized learning. It exported teachers as freely as it had once exported coal. It was a mixed community that for a generation, willingly provided a very significant number of us with a platform or gateway to “other places”.

And so, I have always felt that the move away from the direct provision of State council housing as part of a mixed housing policy to be a strange one: one tinged a little with ideology or the concern of the unknown from decision-makers who had never truly seen it work. I have never either understood the often voiced fears of the “evils” of social housing expressed at public inquiries. That, however, is a debate for another day.

Because, what is certain now, is that the case for the new, large scale provision of social housing by the state via its local authorities has become completely unanswerable. Housing need throughout the UK is at an all time high. House completions, especially of the social rented and affordable housing type are at an all-time low. The Covid 19 pandemic requires government to provide a huge stimulus to the economy ; a C21st New Deal driven by the Planning system. The construction of housing is one of the quickest ways of ensuring that investment in a local economy is optimised through the economic multiplier as well as the swiftest way to meet urgent housing need. Housebuilding undertaken by public bodies is even more directly and immediately effective. It must therefore be an integral part of any rational policy of recovery for the UK.

Even before this pandemic and the very urgent economic need that it generates, local authorities of all political shades had realised that the direct building of council houses was once again a good thing and a necessary thing too. Research undertaken for the RTPI by Professor Janice Morphet in 2019 helped establish that one major reason for the present “housing crisis” was that local authorities had ceased their role of direct housing providers. Since the mid 1980s, she tells us “the shortfall in housing provision has mirrored exactly the scale of the former local authority contribution to the market”.

The RTPI as a result has, just pre-pandemic, produced excellent new practice guidance with a view to supporting an acceleration of the trend to direct provision of council housing by local authorities. Never has such advice been more needed or more directly pertinent.

It points to 5 main reasons why direct Council House building has been growing in recent years. First, the Localism Act added to the legal powers of Councils which, with a degree of imagination and lateral thinking, enabled local authorities to by-pass the previous restrictions on direct council building. Second, Councils have learned from each other and a momentum has built based on success after success. Third, further policy changes have supported delivery including removal of borrowing caps. Fourth, it became apparent that the market and existing policy was not capable of meeting the needs of an area and finally, there has been clear (and expedient) political support from Government for councils to step-up and fill the void left by policy and the market.

Pontlottyn 1983. The Council homes behind the shops and up on the Hill at Brynglas

There was no stigma attached to living in a council house. The majority of pupils in every class in the newly constructed Pontlottyn Junior Mixed School were council-housed. It was a stable, healthy, integrated and forward thinking community: a community that thanks to the new housing, the NHS and the Education Acts looked after itself and prized learning. It exported teachers as freely as it had once exported coal. It was a mixed community that for a generation, willingly provided a very significant number of us with a platform or gateway to “other places”.

And so, I have always felt that the move away from the direct provision of State council housing as part of a mixed housing policy to be a strange one: one tinged a little with ideology or the concern of the unknown from decision-makers who had never truly seen it work. I have never either understood the often voiced fears of the “evils” of social housing expressed at public inquiries. That, however, is a debate for another day.

Because, what is certain now, is that the case for the new, large scale provision of social housing by the state via its local authorities has become completely unanswerable. Housing need throughout the UK is at an all time high. House completions, especially of the social rented and affordable housing type are at an all-time low. The Covid 19 pandemic requires government to provide a huge stimulus to the economy ; a C21st New Deal driven by the Planning system. The construction of housing is one of the quickest ways of ensuring that investment in a local economy is optimised through the economic multiplier as well as the swiftest way to meet urgent housing need. Housebuilding undertaken by public bodies is even more directly and immediately effective. It must therefore be an integral part of any rational policy of recovery for the UK.

Even before this pandemic and the very urgent economic need that it generates, local authorities of all political shades had realised that the direct building of council houses was once again a good thing and a necessary thing too. Research undertaken for the RTPI by Professor Janice Morphet in 2019 helped establish that one major reason for the present “housing crisis” was that local authorities had ceased their role of direct housing providers. Since the mid 1980s, she tells us “the shortfall in housing provision has mirrored exactly the scale of the former local authority contribution to the market”.

The RTPI as a result has, just pre-pandemic, produced excellent new practice guidance with a view to supporting an acceleration of the trend to direct provision of council housing by local authorities. Never has such advice been more needed or more directly pertinent.

It points to 5 main reasons why direct Council House building has been growing in recent years. First, the Localism Act added to the legal powers of Councils which, with a degree of imagination and lateral thinking, enabled local authorities to by-pass the previous restrictions on direct council building. Second, Councils have learned from each other and a momentum has built based on success after success. Third, further policy changes have supported delivery including removal of borrowing caps. Fourth, it became apparent that the market and existing policy was not capable of meeting the needs of an area and finally, there has been clear (and expedient) political support from Government for councils to step-up and fill the void left by policy and the market.

What all of this means is that local authorities are now already directly delivering council homes in numbers not seen for 25 years. And they are doing so with care and quality. The Sterling prize-winning Goldsmith Street development of social housing by the very talented Norwich City Council planning and housing department is but one example of this. There is therefore now a significant direct provision infrastructure in place ready and able to be hugely “ramped up”. This could be done almost immediately. As the RICS research points out, many of the potential council housing sites are already owned by the local authorities and they have developed sophisticated means of ensuring that the planning processes towards delivery are fair transparent and swift.

What all of this means is that local authorities are now already directly delivering council homes in numbers not seen for 25 years. And they are doing so with care and quality. The Sterling prize-winning Goldsmith Street development of social housing by the very talented Norwich City Council planning and housing department is but one example of this. There is therefore now a significant direct provision infrastructure in place ready and able to be hugely “ramped up”. This could be done almost immediately. As the RICS research points out, many of the potential council housing sites are already owned by the local authorities and they have developed sophisticated means of ensuring that the planning processes towards delivery are fair transparent and swift.

Goldsmith Street Norwich. Photo: Mikhail Riches Architects

Therefore, a return to substantial direct government housing grants to relevant authorities as part of a post -pandemic New Deal is essential and urgent. It will allow the infrastructure already in place to scale up direct delivery to a huge extent. It will have an immediate and transformative impact on some of the poorest economies in England and in the devolved nations. It will be among the most efficient ways of both boosting the economy and meeting the growing housing needs of the population. There can be no good reason why such an investment should now be avoided or postponed. The planning system properly-led can once again move quickly and transformatively.

And, let us not forget the work that the Housing Associations have been doing and will continue to do alongside any enhanced direct local authority provision. Their work can also be made much easier. Their ability to borrow to support their activities can at a stroke be massively enhanced by allowing them to ascribe a market value to their assets as part of their dealings with their mortgagees. Very small but critically important and realistic changes to the drafting of the mortgagee-in-possession clauses in most standard s 106 agreements will do the trick to allow this huge amount of additional capital to be released. Strategic Government in London (and elsewhere) has already recognised the importance of this change even if individual boroughs and councils have not all done so yet. But more about this in another piece.

Goldsmith Street Norwich. Photo: Mikhail Riches Architects

Therefore, a return to substantial direct government housing grants to relevant authorities as part of a post -pandemic New Deal is essential and urgent. It will allow the infrastructure already in place to scale up direct delivery to a huge extent. It will have an immediate and transformative impact on some of the poorest economies in England and in the devolved nations. It will be among the most efficient ways of both boosting the economy and meeting the growing housing needs of the population. There can be no good reason why such an investment should now be avoided or postponed. The planning system properly-led can once again move quickly and transformatively.

And, let us not forget the work that the Housing Associations have been doing and will continue to do alongside any enhanced direct local authority provision. Their work can also be made much easier. Their ability to borrow to support their activities can at a stroke be massively enhanced by allowing them to ascribe a market value to their assets as part of their dealings with their mortgagees. Very small but critically important and realistic changes to the drafting of the mortgagee-in-possession clauses in most standard s 106 agreements will do the trick to allow this huge amount of additional capital to be released. Strategic Government in London (and elsewhere) has already recognised the importance of this change even if individual boroughs and councils have not all done so yet. But more about this in another piece.

Brynglas housing Pontlottyn 2019

For now, the message is simple. We need positive leadership. We need an holistic C21st Roosevelt-like “New Deal” where the DHCLG takes the lead, acting as a Department of Recovery and Reconstruction meeting existing housing and infrastructure needs in a way which will also aid a swift recovery. An essential part of that New Deal will involve the State, through its local authorities, building on existing good practice and once again, urgently, facilitating the construction of many more high quality “council homes” for its hard pressed and economically challenged communities.

Russell Harris QC

Brynglas housing Pontlottyn 2019

For now, the message is simple. We need positive leadership. We need an holistic C21st Roosevelt-like “New Deal” where the DHCLG takes the lead, acting as a Department of Recovery and Reconstruction meeting existing housing and infrastructure needs in a way which will also aid a swift recovery. An essential part of that New Deal will involve the State, through its local authorities, building on existing good practice and once again, urgently, facilitating the construction of many more high quality “council homes” for its hard pressed and economically challenged communities.

Russell Harris QC